On a scorching August afternoon, University of North Carolina women’s lacrosse coach Jenny Levy tours Chapel Hill’s verdant college campus with a top recruit she hopes to woo into her elite program. Levy and her prospect happen upon a group of Levy’s varsity team players, running through drills at an unofficial preseason practice.

You’d think the top tier NCAA Division I coach would be elated. Her girls are out there, pounding the grass in what feels like an almost scripted display of off-season initiative. But Levy has mixed feelings. “I’m glad they’re out there training, but I’d be much more excited if they had flipped their goals upside down or placed them back-to-back to mix things up a bit,” she says. “They are kind of like overbred dogs, mimicking the drills we run twice a week in practice. They do what they know. What’s safe. I’d much rather see them trying something totally outrageous and different. I want them to get creative on that field.”

It’s Levy’s biggest challenge: to force her hyper-trained, over-taught players to think on their feet, to play creatively. She spends hours designing and redesigning her practices to address this deficiency head-on. “Unless they had an amazingly creative youth sports coach—and most haven’t—kids simply aren’t wired to think creatively in game situations,” she says. “Starting at a very young age, there’s always been an adult telling them what to do, where to stand, when to move. They may be talented, or physically fit, but if I want them to be creative, I have to retrain them.”

To combat this dearth of creativity and adaptability, Levy constantly changes the rules and parameters of drills and games. She jostles her players out of their comfort zones and forces them to adapt instantaneously to revised circumstances. For example: On a traditional lacrosse field, two six-by-six-foot goals face each other at opposite ends of a 100-yard field. “So I’ll use four goals instead of two and place them all over the field rather than directly opposite each other,” says Levy. “Suddenly players can score in different ways. When you change the dynamics, you force them to think differently, to adapt. To devise ways to adjust. Change the space. Change the equipment. Change the rules. Then do it again. We’ll alter the dimensions of the field, or the location of the goals. We might use tennis balls instead of lacrosse balls. The key is to switch things up on them so that they always feel a little bit uncomfortable and have to figure things out for themselves.”

Levy is not the only educator grappling with recruits who lack creativity and adaptability. This is a cross disciplinary concern. Kevin K. Parker, professor of bioengineering and applied physics at Harvard, says it takes him years to deprogram students who have been taught in conventional classrooms. Only then can they become innovative, creative thinkers in a laboratory setting. “One of the biggest challenges I have is taking [those] straight-A students and pulling them outside the box. They are raised in a classroom making straight A’s. You ask them into a lab, and you are asking them to tear apart everything they know, everything about their safe zone.”

At Stanford University, Dr. Carol Dweck encounters students who want to look smart rather than get smarter. In her book Mindset, she sets out a thoroughly researched case of how overpraise, overtraining, and over structuring can produce young people who do not live up to their potential. “In fact, every word and action sends a message,” she says. “It tells children—or students or athletes—how to think about themselves. It can be a fixed mindset message that says: ‘You have permanent traits and I’m judging them.’ Or it can be a growth mindset message that says: ‘You are a developing person and I am interested in your development.’”

Too often our child-athletes have been similarly overprogrammed and overtrained, starting at too early an age. Whole Child Sports wants to change that. We recommend a timeline that respects and promotes the free play and game play stages of a child’s personal and athletic development, pivotal phases in which children can learn and cultivate attributes essential to their future success on the field and beyond.

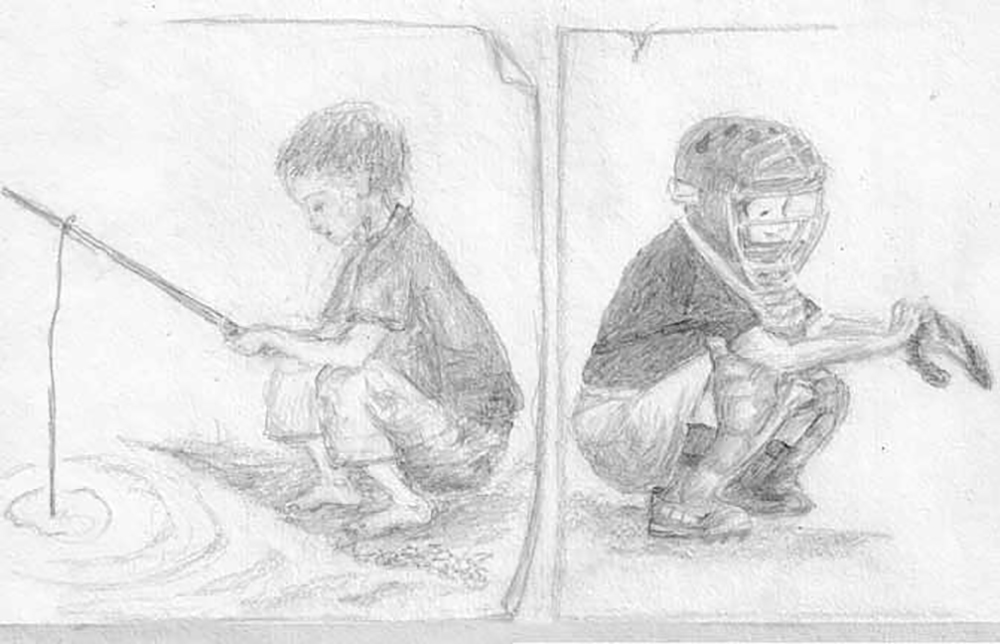

We are not way out on a limb here. There is nothing radical or granola / tie-dye about what we suggest. Child development experts—or play theorists—have touted the benefits of informal sport and game play since the early 1960s. Think sandlot baseball in middle America or pickup pond hockey in colder climes; beach and alleyway soccer in the favelas of Brazil, and baseball played with bottle cap “balls” and broomstick “bats” in the backwater towns of the Dominican Republic. These settings are the contextual equivalent of superlabs, where überathletes like Satchel Page, Wayne Gretzky, Pelé, and Vladimir Guerrero developed and honed the skill sets and creative flair that catapulted them to superstardom. “The best athletes in the world have had formal training at some stage, but what distinguishes them from the rest is what they did as kids when they were alone or with friends, just messing around,” says Levy. “Like backyard ball, where they worked on skills naturally. Not surrounded by cones and barking adults.”

Sadly, such natural developmental petri dishes are a rarity today. Probably like you, back when we were growing up, the opportunities for free play and games were plentiful. All you had to do was step out your back door, rustle up some friends, and get on with it. We’d lose ourselves for hours on end, often returning only as darkness fell or the call to supper rang out. For many those days are gone. Perhaps Dr. Neil Roth—youth sports medicine specialist and father of two—characterizes it best: “In my neighborhood you went into the street and found friends who were out and did whatever. Climb trees. Play ball. There is none of that going on in my community today. I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve seen kids in our neighborhood go out and just have completely unorganized, unstructured play time.”

Where did all the children go? And why? Take a drive through urban America or suburbia, and you can bear witness to the nearly empty parks and derelict outdoor facilities. There is little going on out there that isn’t organized and run by adults. As Mike Lanza, author of Playborhood: Turn Your Neighborhood into a Place for Play, points out, “Kids are typically doing one of two things these days. They are either sitting in front of screens too much—up to eight hours a day on average. Or they are being chauffeured around to highly structured, adult-led activities.”

One reason why is that parents are struggling to overcome their fears. Child safety is foremost in our minds, and mostly with good reason. Many neighborhoods are unsafe. But even in secure areas, few kids are permitted to wander, and typically the kid who walks around the neighborhood is unlikely to find anyone else to play with anyway. The very fact that a Mike Lanza exists—someone who has created a micromilieu in which his kids and all the children in his immediate neighborhood can gather the way we all did every day as kid—is emblematic of how radically things have changed, and most would agree this change has not been for the best. It’s almost unbelievable that a dad who wanted his kids to experience self-directed fun could be such an outlier. ♦

From Kim John Payne, Luis Fernando Llosa, & Scott Lancaster. Beyond Winnning: Smart Parenting in a Toxic Sports Environment (Lyons Press, Connecticut, 2013)